I’ve been on a bit of a journey over the past few years discovering the music of Pittsburgh rapper Mac Miller. Long story short: Like everyone else in Pittsburgh, I was aware of Mac’s success, but I was also (like many others) guilty of dismissing him as just another mediocre white rapper. That changed when I finally started paying attention to him, after learning from a local radio program that he had passed away — and the music I heard during that tribute was anything but mediocre.

The truth — revealed by a barrage of mixtapes, albums, features, freestyles and interviews — was that Mac Miller was a consummate artist. He had bars that ranged from funny to tender to tragic. He played multiple instruments, made beats, and produced. He was fully committed to his creative vision, putting in the work to make it reality. And he was also, like so many of us, at the mercy of his mental health issues.

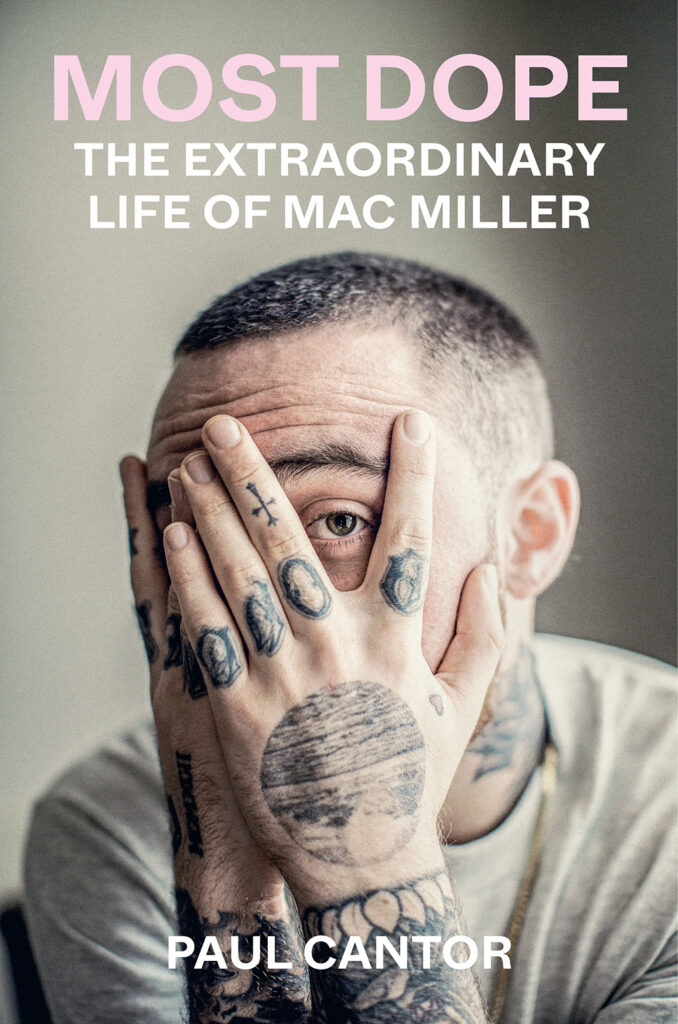

Most Dope attempts to tell the story of a remarkable person who left us too soon. The author, Paul Cantor, necessarily had to make some tough choices about how to approach such a complex subject. Some of those choices were successful while others were not. For example: Cantor spends a few pages early on putting Mac’s whiteness in context within hip-hop culture. Those pages were well spent, since a big part of Mac’s story is an attempt to shrug off people’s preconceptions and gain acceptance. A similar effort was made to orient readers who were unfamiliar with Pittsburgh and its history — but, hard as it is for me to admit, the fact that Mac Miller was from Pittsburgh is just not that important to his story. The author dedicating a long section early in the book to the details of the founding of the neighborhoods of Point Breeze and Homewood almost made me put it down. Almost.

This book was written without the blessing of Mac’s family, who instructed people who knew Mac not to talk to the author. I’m not sure of the reasons, but I’m grateful that many people still agreed to go on the record. Those interviews, combined with accounts from other sources, helped Cantor flesh out Mac’s story from the early days of his career through his untimely death from an accidental drug overdose at 26.

Ultimately the story is a tragic one, but unlike other stories of addiction, it’s not tragic because of wasted potential. Mac applied his potential and achieved greater success than anyone expected. Instead, his story is tragic because it was cut short. We glimpsed what he was becoming, but the transformation was never completed. Mac battled addiction, gambled with the substances and amounts he was consuming, and came close to the line on several occasions — but in the end, what killed him was unknowingly taking fentanyl. This wasn’t a suicide or even an uncharacteristic lapse in judgement. Mac was an addict, stuck in the cycle of recovery and relapse, hoping to really kick the habit some day, but finally done in by tainted drugs.

Fans like me who came to love Mac’s music will never have all the answers. We’ll always wonder what he might have done had he lived. Books like Most Dope can’t answer that question, but they can help us fill in the blanks about this person we feel a connection with. Maybe, eventually, with more accounts like this and the passing of time, we’ll find some closure.